Tropes. We hear about them all the time. When you query agents, you’re advised to know your tropes and pitch them; the same thing with social media marketing, especially on Instagram and BookTok. And of course, when you’re doing the most important thing–writing–you’re encouraged to utilize popular tropes to win over readers as you compose your manuscript.

It’s kind of daunting, isn’t it? And where did all of this trope stuff come from, anyway?

Some people believe that the tropefication of book content and marketing started in fanfiction — and they wouldn’t be entirely wrong. Long before the bookish community adopted tropes, fanfiction authors and readers used tags to signal what the readers could expect within their fics.

And they got extremely specific as well. Tags like “only one bed”, “slow burn”, and “friends to lovers” (as well as tags about sexual acts that happen within the fic) were always highly popular. Each author could also get even more specific — for instance, they could say “X character is tired” or “X character really needs a hug” (there are so many more, and they’re often very funny).

Obviously, as the bookish and fanfiction communities often intersect, the terminology of some of these tags was easily adopted and adapted to fit original works. (P., 2023, par. 19-21).

Another theory is that the romance genre inspired trope marketing.

The romance genre is massive and one of the most commercially viable in the book industry.

If you look at the marketing of romance novels compared to many others, you’ll notice that it heavily relies on mentions of tropes and clichés to ensure that the story reaches the intended reader.

[…] Readers usually want to know what tropes are included in a book pretty early on in a book. Whether it’s enemies to lovers, star-crossed lovers, childhood sweethearts, or second-chance romance, readers crave the same type of stories (Huddleston, 2023, par. 5-6; 8).

I couldn’t find an exact time period for when trope marketing took off–some sites said it’s been around for the past 10-20 years; others say it took off during the COVID years (starting in 2020); meanwhile there’s also the suggestion trope marketing came about when BookTok became lucrative around 2020-2021.

The most popular tropes (according to my cursory research and reading experiences) are pretty much romantic ones:

Happy Ending

The Love Triangle

Forced Proximity

Forbidden Love

The Enemies to Lovers

Fake Relationship

Incapable of Love

Love Is the Answer

Instalove

Marriage of Convenience

Unexpected Love Interest

Fated Mates

Misunderstanding/Miscommunication

Who Did this to You?

Touch Her and Die

Hurt/Comfort

Knife to the Throat

Only One Bed

Grumpy/Sunshine

Found Family

Slow Burn

A lot of the tropes listed above came from Kindlepreneur but I threw in some I’ve seen on BookTok and Instagram, too.

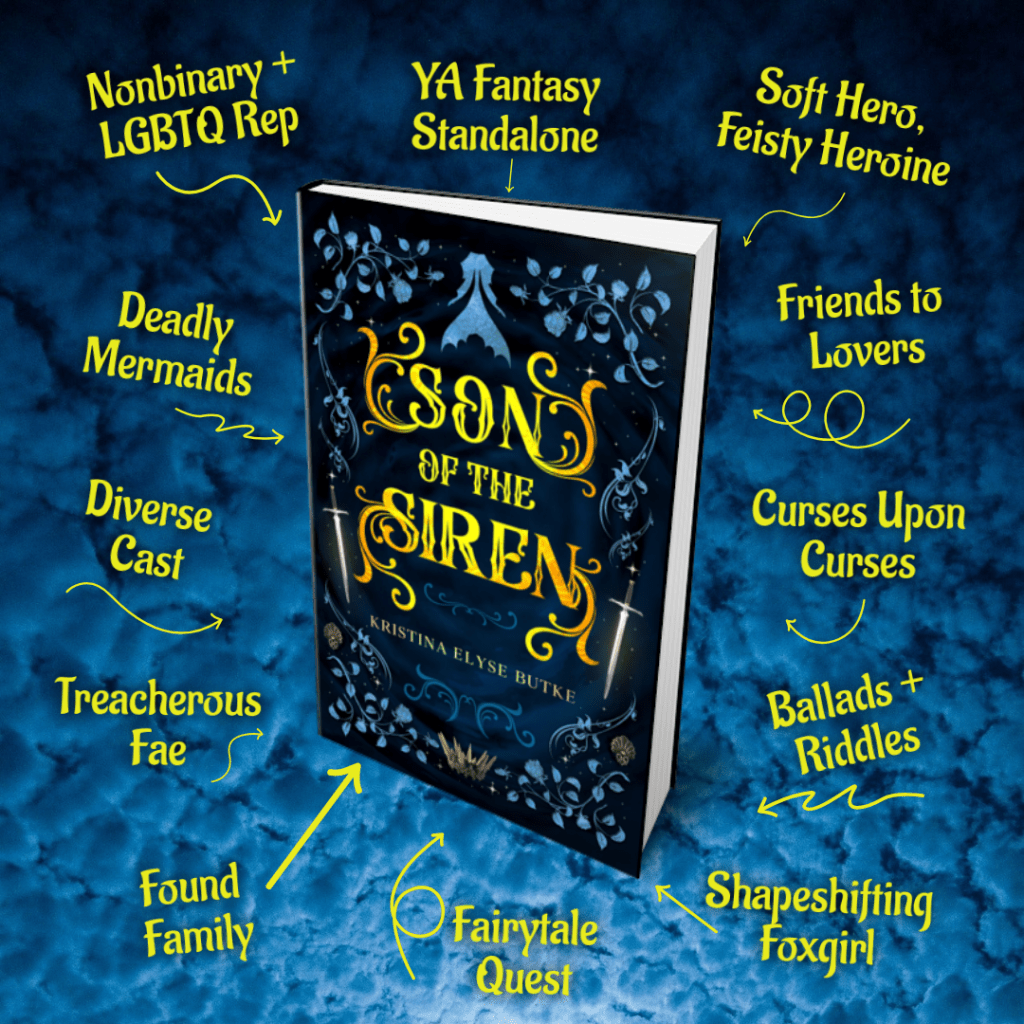

Anyway, over the years I’ve seen what are called trope maps proliferating social media. To be honest, readers, I debated long and hard about making one of my own for Son of the Siren (you can see it in the trope map collage above). This was because I didn’t rely on tropes all that much for my book, so I had a hard time coming up with stuff, and…there’s a lot of negativity around trope marketing!

When books become tropified, they lose their individuality and, rather than following the plot listed on the back of the book, are forced to fit into the cookie-cutter design of their assigned trope. They can be nothing less and — more often than not — nothing more. When novels are defined by clichés, they inherently lose their unique capability to transport you into a new world. Is this not doing a blatant disservice to the reader? Similarly, the hours upon hours that authors have put into their work will be watered down to a phrase used to define hundreds of other books. It may sell more novels but the satisfaction of completing one’s own creative piece of work will be lost in the noise (Pathak, 2024, par. 4).

Here’s another perspective:

The same aforementioned tropes, along with many others, have become more elaborate and over-saturated, leading to the introduction of hyper-specific moments in books that, ultimately, oversimplify literature. For example, two popular subcategories of the “enemies to lovers” trope are the “one bed” and the “who did this to you?” tropes. The former is self-explanatory: two love interests are forced in an environment where they must share a single bed. The latter occurs when the main character—usually a woman—is hurt and her love interest, an incredibly hot and possessive man, asks who caused her harm. Some other honorable mentions are “knife to the throat” (yes, that’s a real thing), “fake dating,” and “touch her and you die” (also real).

Don’t get me wrong—I’d be lying if I said that many of these tropes aren’t guilty pleasures of mine. They can offer an enjoyable escape, allowing me to switch off my brain and indulge in a light, cheesy read without worrying too much about the plot or being blindsided by unexpected twists. But it’s still clear that these hyper-specific tropes often serve as a cash grab by authors who know they will sell (Mayeaux, 2024, par. 3-4).

I would say that the “cash grabbiness” is coming more from the publisher than the author, but then again…lots of marketing is pushed on the author, so maybe there is some truth here. I know that when I made my trope map for Son of the Siren, it’s because I wanted to get people interested in the book and to yes, buy it.

Here’s another observation:

The issue is that books are now being written and marketed as if they are made for BookTok, manufactured to fit the app’s specific audience and trends. Popular tropes such as ‘slow burn’ or ‘enemies to lovers’ dominate the industry, as well as very specific ones (called microtropes) like: ‘who did this to you?’, ‘touch her and you die’, ‘knife to throat’, ‘only one bed’ etc. This may seem harmless at first, but when we read, recommend and write books this way, we no longer read stories. We are reading a compilation of tropes, stacking them on each other like you would build a burger or choose the toppings on your froyo cup.

On a storytelling level, marketing and buying books in an increasingly tropified industry zaps any tension out of the story. When you pick a new book up, you already know, for example, that the two main characters who don’t see eye-to-eye will eventually fall in love because it’s been marketed as an ‘enemies to lovers’ story. You also know that one main character will have a villain arc because there is a trope template on the author’s Instagram page that says so. Although this might help those who wish to find a specific trope or story, it becomes a slippery slope when tropified books start to lose diversity, individuality and the readers’ anticipation (Rusady, 2024, par. 6-7).

I kind of agree with these observations. While tropes can tell you what a book is about in .5 seconds, it can leave out the meat of the story. While it helps markets books that fulfill specific reader desires, it oversimplifies the text.

When I set out to make my trope map for Son of the Siren, like I mentioned before, I didn’t have enough tropes to fill it, but at the same time, there was an over-reliance on playing up the tropiness of the book.

I have since deleted the first trope map I made because I found it unsuccessful for marketing, and it really didn’t communicate what all was in the book. So, the trope map graphic I made had a smidgen of tropes and more general content. Here’s a bigger image of it:

Obviously LGBTQIA rep is not a trope and it’s rather insulting to consider it as such. But readers were really appreciative of seeing diverse rep and it was suggested to me that I share how that was a significant part of the book. So again, not tropes, but still a visual clue as to what the book contains.

I’ve been thinking about what to make for The Name and the Key. There will be a trope graphic for each book, yes. I’d like to experiment with a trope graphic for the first book now, but I’ve got to wait until we have a book cover. I get to practice patience, yay!

Readers, what do you think about the tropification of books and book marketing?

References

Chesson, D. (2025, June 23). Book tropes: Everything you need to know (complete list). Kindlepreneur. https://kindlepreneur.com/book-tropes/

Huddleston, P. bySteph. (2023, February 14). Are tropes and cliches always a bad thing? romance genre spotlight. Steph Huddleston. https://stephhuddleston.com/2023/01/31/are-tropes-and-cliches-always-a-bad-thing-romance-genre-spotlight/

Mayeaux, V. (2025, March 13). The trope-ification of books is literary brain rot. The Broken Plate. https://thebrokenplate.org/the-trope-ification-of-books-is-literary-brain-rot-by-victoria-mayeaux/

P, K., & Review, P. (2023, December 23). Marketing books through tropes and how it affects the publishing industry. Bookish Delights. https://www.bookish-delights.com/marketing-books-through-tropes-and-how-it-affects-the-publishing-industry/

Pathak, A. (2024, February 1). How tropes are watering down Modern Literature. The Michigan Daily. https://www.michigandaily.com/arts/books/are-tropes-ruining-books/

Rusady, J. (2024, September 9). The rise of the reader aesthetic: Booktok and book tropes. Grattan Street Press. https://grattanstreetpress.com/2024/09/09/the-rise-of-the-reader-aesthetic-booktok-and-book-tropes/

Leave a comment