I wrote about alchemy in this post: Alchemy and The Name and the Key. I recommend giving that a look so you can understand how I’m using alchemy as the major magic system in my trilogy!

I was drawn to learning about alchemy thanks to Hiromu Arakawa’s masterpiece Fullmetal Alchemist. I’ve watched both anime adaptations of her work (I do find Brotherhood to be the superior choice) and the imagery in the anime, along with alchemical lore, made me want to learn more about it.

But alchemy is a bit…tricky. It is ancient, with versions in Africa, Asia, and Europe. What unites them are the idea that you can, through chemical refinement of primal substances, create a way to eternal life. Some cultures believed that way is through the philosopher’s stone. Other cultures take a more esoteric look at it, making alchemy more spiritual than literal.

Literal! Ha! What am I saying? I’ve read about alchemy through wikis and encyclopedias and copies of primary sources, and there is nothing literal about alchemy. Everything is an image, a metaphor. Nothing is all that straightforward.

Take The Twelve Alchemical Gates that appear in George Ripley’s The Compound of Alchymy. Published in 1591, it’s considered a major document that explains the chemical processes of the Great Work, or Magnum Opus, which leads to the creation of the philosopher’s stone. This is an excerpt from the First Gate (chemical stage), Calcination.

Ioyne kind to kind therefore as reason is,

For euery burgeon answers his owne seede,

Man getteth man, a beast a beast I wis,

Further to treate of this it is no neede.

But vnderstand this poynt if thou wilt speede,

Each thing is first calcined in his owne kind;

This well conceaued fruite therein shalt thou finde.

To paraphrase, calcination is where you heat a substance to bring out a change in its physical or chemical constitution. It removes water and volatile substances or it oxidizes the substance. Another name for calcination is purification, which is interesting because in the more spiritual/esoteric forms of alchemy, the goal is to purify and refine oneself in a process that leads to immortality. In the chemically-focused type of alchemy, you are trying to bring out the perfect substance, which is the philosopher’s stone.

The above section states that “everything is calcined in his own kind / this well-concealed fruit therein thou shalt find.” While Ripley is writing a manuscript advising alchemists how to make a philosopher’s stone, he has comments like this throughout. Is he really talking about a chemical reaction anymore? Humans don’t burn themselves to change their physicality (although in The Name of the Key, they do), so Ripley must be referring to purification here, and something hidden inside all of us that is a worthy reward.

So many alchemical texts are like this. You think they are talking about one thing, and then they turn around and mean something else. The same thing goes with alchemical imagery.

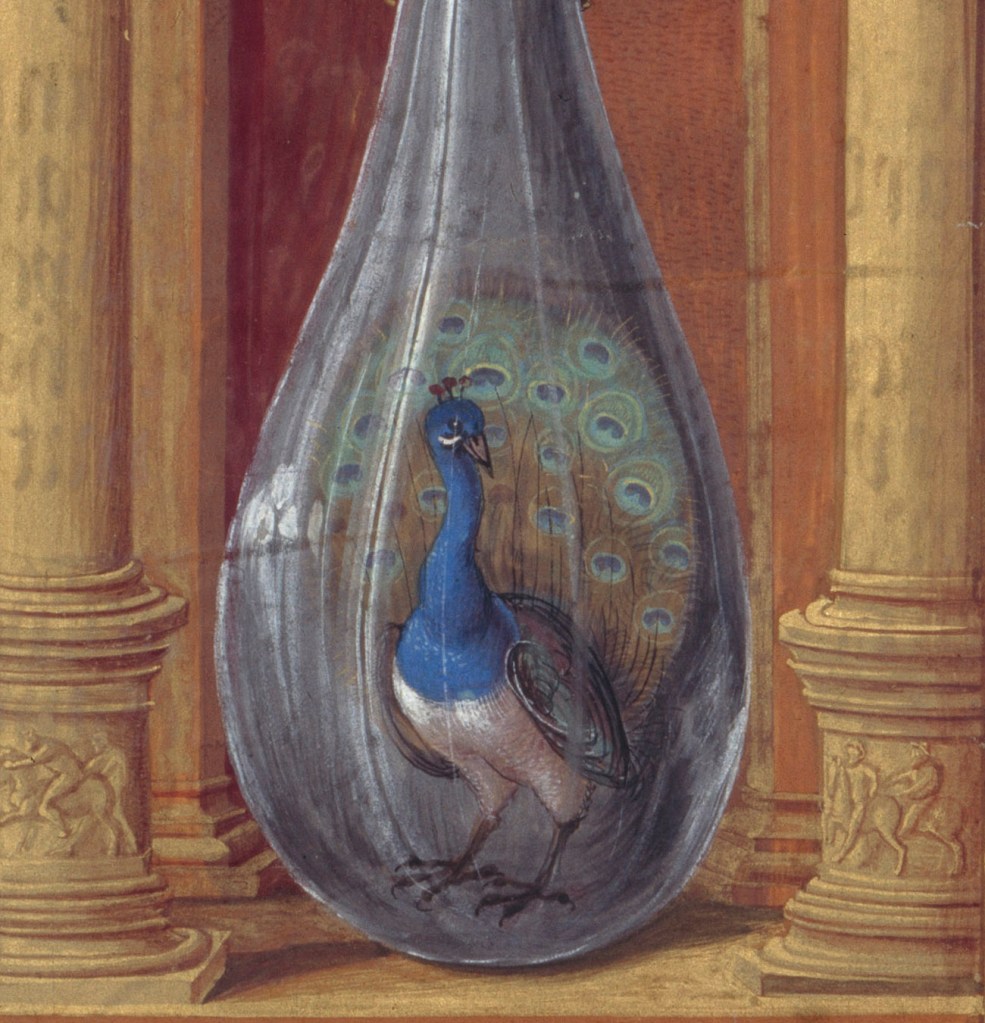

To state the obvious, you cannot put a peacock in a flask. This image is a metaphor for a chemical reaction known as the Cauda Pavonis. Also known as the Peacock’s Tail, this is what you are supposed to see after you complete the alchemical step known as Sublimation. To quote Wikipedia because I am lazy,

Sublimation is the transition of a substance directly from the solid to the gas state, without passing through the liquid state.

In the alchemist’s flask, this creates a solid, black, greasy substance. Right after that, there’s supposed to be a flash of iridescence, something rainbow-like…and this is the Peacock’s Tail.

So…how easy do you think it was for me to explain all of that?

I’ve been reading up on alchemy for a long time, but I frequently have to consult and reconsult sources, because I’m worried about messing things up. The trick is for me to make alchemy comprehensible to my readers. They need to be presented with information in a digestible way, or else I’ll lose them.

I have a scene in The Step and the Walk in the classroom at the University of Evandra where Andresh is studying manuscripts from The Great Rebirth era (the equivalent of the Renaissance in Europe). An alchemical text was chosen for the class to interpret based on imagery and metaphor. I had the fun task of making the Cauda Pavonis palatable to my readers, but also write about it in rhyme.

Here’s what I came up with:

Splendid Solis shines in Glas,

After blackness phase doth pass.

The Peacock’s Tail, immortal Age,

Nigredo to Albedo stage.

Cross Black Gate and Rainbow see,

Whiteness soon be clear to Thee.

I’m giving a nod to some alchemical art, and then the four stages of alchemy (this is a different interpretation from Ripley’s Twelve Gates–the four stages are nigredo, albedo, citrinitas, and rubedo, aka black, white, gold, and red).

This was not easy to come up with, and I felt like I needed to make the alchemy understandable to readers while being true to the history of this pre-science art.

The question is, can I do this throughout the book, and to do so without info-dumping? It’s hard for me to say at this juncture because I just started writing the book.

It’s going to be a fun challenge, though.

Leave a comment